How are wars waged today compared to in previous decades?

A key difference is the emergence of drones and artificial intelligence. Warring states have become increasingly dependent on systems controlled by global oligarchs. Most recently, Ukraine found itself at the mercy of the Starlink satellite network, owned by controversial American billionaire Elon Musk.

In the 1990s, two influential American works tried to predict the new world order: Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History—which envisioned the irreversible triumph of liberal democracy—and Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations, which foresaw future wars not between states, but between cultural blocs. If we were to look back in 2024 and “play generals after the battle,” which one was right—Fukuyama or Huntington?

Neither. While states may often refer to civilizational or religious differences, as Huntington predicted, they still primarily pursue national interests and play all sides accordingly. Just look at Erdogan’s Turkey, Mohammed Bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia, or Vučić’s Serbia.

The same goes for Fukuyama’s liberal vision, which imagined the unstoppable global spread of human rights and democracy. Today, Biden and Blinken justify U.S. involvement in conflicts as a defense of democracy against autocracy, and of human rights against tyranny. However, behind this moral façade lies a strategic attempt to preserve—or at least slow—the decline of American global hegemony. Again, it’s all about national interest.

Can we say, then, that the human rights doctrine has failed in its quest for global expansion?

We must first acknowledge that the limited successes of the human rights doctrine have always been tied to the unipolar dominance of the West, led by the United States. Since the early 2010s—when China became the world’s second-largest economy, Putin returned to the Kremlin, and the Arab Spring ended in either renewed dictatorship (as in Egypt) or civil war (as in Libya and Syria)—this unipolarity has been gradually giving way to what some analysts now call “apolarity.” The United States remains the most powerful state and, thanks to its global military presence, the only true superpower. But its ability to control developments in strategic regions has significantly weakened.

If we as humanity were to abandon the human rights doctrine, what might replace it?

The most likely alternative is the rise of national conservatism, which has already been flourishing amid the collapse of Western hegemony. Conservatives blame the West for “civilizational suicide,” supposedly caused by an excess of liberalism, human rights, and political correctness.

If this trend continues, we will see new regimes and alliances built on various blends of traditionalism and authoritarianism. The rights of individuals and minorities—ethnic, religious, gender, or sexual—will be eclipsed by the rights of national majorities to preserve their traditions and, in the words of Donald Trump, “make their nations great again.” Collective identity will take precedence over shared humanity, and mutually exclusive national narratives will triumph over the universality of human rights.

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek uses the term “hot peace” instead of “cold war.” Is that an accurate description of today’s military conflicts between the spheres of Western and Eastern influence in this changing global order?

As always, Žižek’s clever inversion contains a grain of truth wrapped in a misleading analogy. The misleading part is the comparison to Cold War bipolarity. Given the “multi-azimuth strategy” pursued by key states in strategic regions, it’s no longer accurate to speak of Western and Eastern spheres of influence. Is Saudi Arabia—in addition to Israel, the main pillar of U.S. power in the Middle East—part of the East or West? It achieves its national goals by aligning with both sides. The same can be said of Turkey, or even India. The strategic ambiguity of these states makes the concept of fixed spheres of influence obsolete.

That said, the grain of truth is this: just as the United States and the Soviet Union once avoided a third world war out of mutual self-interest, today’s regional and global powers also seem motivated to avoid open conflict.

Which powers are you thinking of specifically?

Take the Middle East, for example. Israel has spent months trying to provoke Iran and the United States into a regional war—one that could easily escalate into a global conflict and reinstate a kind of bipolar order. This would benefit Israel strategically, positioning it once again as “the West’s island in the Orient,” to borrow from Theodor Herzl. It would also help ensure that Western countries wouldn’t abandon it for reasons of national interest.

However, so far, the U.S., Iran, and Hezbollah (Iran’s proxy on Israel’s border) have all done their best to avoid such a war. Whether they succeed will be seen during these days.

In short, most actors today benefit more from maintaining a state of “neither peace nor war” through hybrid tactics—targeted assassinations, sabotage, weaponized migration, cyberattacks, and the like. This is likely what Žižek means by “hot peace.”

As citizens of the Global North, we often overlook key developments in the Global South. Which conflicts are escaping our attention while most eyes are focused on Russia’s war in Ukraine and Israel’s assault on the Palestinian territories?

Czech attention tends to stray from conflicts where the West has no “iron in the fire,” unlike Israel in the Middle East. The brutal suppression of the uprising in Ethiopia’s Tigray region by President Abiy Ahmed has barely been covered in the Czech media. Nor has the simmering civil war in other parts of Ethiopia, such as the Oromia region. The death toll from the war in Tigray has likely reached tens, if not hundreds, of thousands, and it has brought with it the renewed threat of famine.

Similarly, the war between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, which began in April 2023 and is still ongoing, has received little media attention. This conflict has already produced an estimated ten million refugees, reignited ethnic massacres in Darfur, and—like the war in Ethiopia—created the risk of mass starvation.

Is religion, geopolitics, economic interests, or climate change the dominant cause of global conflicts today? Also, is the order of their influence changing?

It is usually a mix of these factors—though not always all of them—and their relative weight varies depending on the specific context. We should not overlook conflicts related to the exploitation of natural resources, which have long fueled, for example, the war in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Incidentally, this is another major regional conflict that receives hardly any attention in the Czech Republic.

What impact do current conflicts have on global capitalism?

If they remain localized on the periphery (like the aforementioned conflict in Congo), then the looted goods and dirty money they generate can easily be funneled into and laundered through global flows of goods and capital. However, once these conflicts move closer to global centers or threaten entire regions, they begin to disrupt the smooth functioning of modern capitalism.

This fact, by the way, helps explain China’s official neutrality in the Russia–Ukraine war. While China is de facto aligned with Russia—through massive supplies of dual-use technologies and raw material extraction—it has no interest in the continuation or escalation of the conflict. China’s global power rests on economic growth tied to the functioning of global capitalism, which it fully embraced after joining the World Trade Organization in 2001.

What is the role of women and children in wars? Would there be fewer wars if women ruled?

Certainly not. Unfortunately, at least since the time of Magda Goebbels (who was not the only “Nazi fury”), we know that women are capable of joining one side or the other in modern warfare with the same ferocity and ruthlessness as men.

At the same time, the fate of women caught in current conflicts is often worse than that of men, as they are frequently victims of sexual violence—currently being used as a weapon by members of the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces.

And what is the fate of children in war conflicts? What influence does the current war have on the fate of future generations?

The permanently debilitating effects that wartime violence can have on children—even when they survive without physical injuries—are well documented, not least in the work of neuropsychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik. As a Jewish child, he survived an attempted deportation to a death camp in Nazi-occupied France.

As early as the 1990s, Cyrulnik warned that Israel’s counterterrorism measures in the occupied territories exhibited elements of collective punishment and posed a threat to Israel’s own security by planting the stigma of powerlessness in the minds and hearts of Palestinian children. It is hardly surprising, then, that some of these children may grow up and attempt to “overcome” this stigma through acts of terrorist violence directed at Israelis. His insight suggests that the logic of collective retaliation cannot guarantee Israel’s safety; on the contrary, it exacerbates the very threat it seeks to eliminate—it fuels the fire of terrorism.

The actions Cyrulnik criticized 25 years ago pale in comparison to what we’ve seen in Gaza over the past year—that is, if one watches British or French news rather than CT24.

Israel may have succeeded in dismantling most of Hamas’s military capabilities and organizational structure, but by killing and collectively punishing the civilian population, it has planted the seeds of hatred and radicalization in the hearts of future generations of Palestinians.

Can you imagine a world without war?

I have been very pessimistic since Putin's attack on Ukraine in February 2022, the Hamas massacre a year ago, and the subsequent Israeli retaliation. These and other wars in recent years only prove what some military theorists and historians of war have been saying for a long time: the industrialisation of killing technology and democratic politics have turned the war of rulers into a war of nations, including civilians. This has caused wars to form an unstoppable tendency towards becoming all-encompassing, causing more and more casualties on the side of civilians than combatants.

In other words, under current conditions, it is impossible to wage war in a chivalrous, clean manner. Furthermore, the extent of a war’s destruction is such that it can hardly be rationally defended as a “continuation of politics by other means.” Once a war is in full swing, its consequences usually cause such immense damage, even to the victor, that he ends up being worse off than before the war.

Not idealistic delusions, but precisely this realistic and rational statement should lead us to strive to build an international order that would function without war.

Something like a new UN Charter?

The 1945 UN Charter was, in fact, an attempt to create such an order. However, from 1948 to 1989, the realization of global peace was obstructed by the Cold War’s bipolar structure. The subsequent attempt to secure lasting peace through Western unipolarity between 1989 and 2011 also failed. Instead of peace, we saw wars waged in the name of human rights and democracy in Afghanistan and Iraq. These wars led to hundreds of thousands of deaths and inflicted immeasurable damage—far exceeding the suffering caused by the undemocratic regimes the U.S. overthrew.

In Afghanistan, the same regime returned to power after exactly twenty years, reinstating its misogynistic tyranny. Not only did Western hegemony fail to fulfill the UN Charter’s ideals—which had previously been obstructed by bipolarity—but since that bipolarity ended, the U.S. has blocked every UN Security Council resolution condemning the killing and torture of civilians in Gaza. Russia has done the same in blocking resolutions condemning its aggression in Ukraine.

In this way, for the past two years, two permanent members of the UN Security Council have worked actively to reduce the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Genocide Convention to mere scraps of paper.

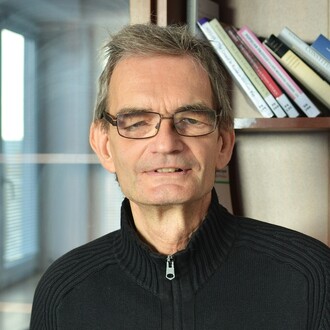

Pavel Barša will speak at the Inspiration Forum in the program War Without Rules: On the Future of Conflict in a Changing World (Saturday, November 2nd, 12:30 - 2:00 PM).

The interview was originally published in Deník Alarm.